The New York Review of Books published a review-essay about Leah Broad’s Quartet in their issue dated October 5, 2023 (published online in mid-September), and while the bulk of the reviewer’s attention went to Dame Ethel Smyth—whose success at eating all the oxygen in any room she’s let into remains unparalleled—a number of statements were made about Rebecca Clarke, virtually all of them untrue, and most of them plainly lifted, not from Dr. Broad’s book, but from Wikipedia.

Well, this wasn’t our first rodeo, so we weren’t particularly surprised, even though the reviewer is Distinguished Professor of Music History and Dean Emeritus at a well-known American university, and probably wouldn’t tolerate such behavior from his students. What stuck in our craw, however, was not the ahistorical and overwhelmingly reductive treatment of Clarke’s output and publishing-history, but the final as-if silver lining—”Fortunately her works are being championed and the unpublished pieces brought into print by the recently formed Rebecca Clarke Society at Brandeis.”—giving credit to a scofflaw outfit that has been the principal impediment to the publication of Clarke’s works for the last two decades.

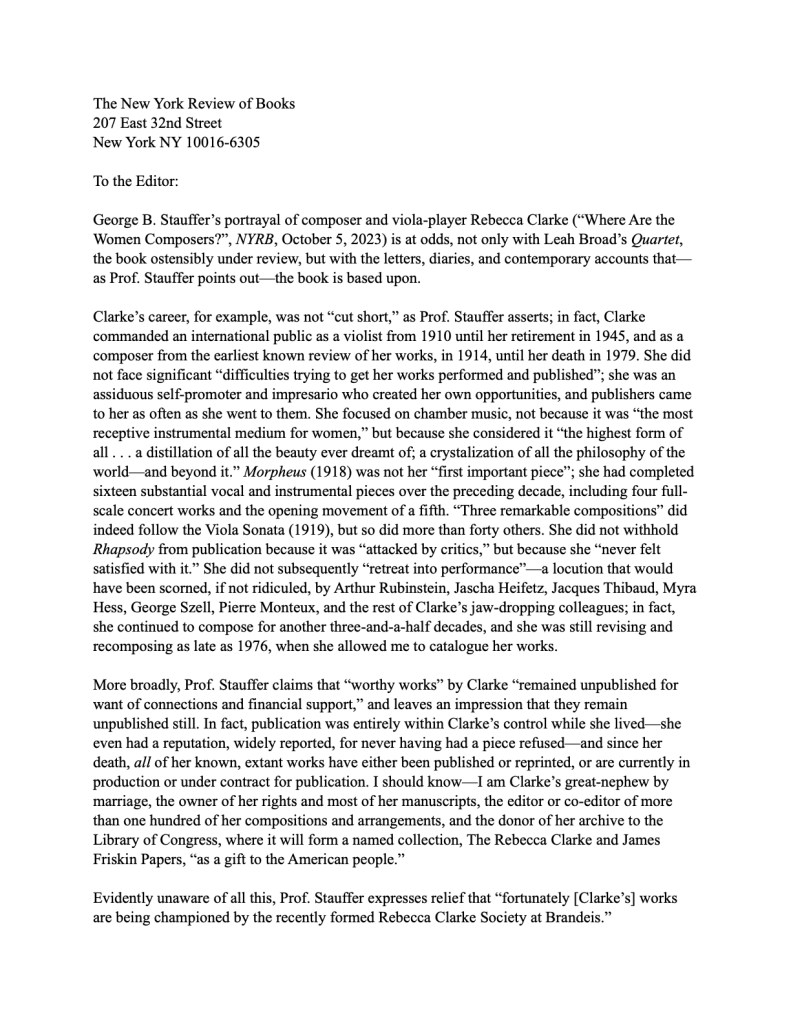

Clearly, this required a response, so we contacted the Review immediately with the relevant facts. This yielded a slight correction, deleting “and the unpublished pieces brought into print” from the body of the review, and adding a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it line at the end, reading “An earlier version of this article misstated the purpose of the Rebecca Clarke Society at Brandeis.” Well, no, actually—both versions of the article misstated the facts of the matter across the board, so we submitted a formal letter to the editor, and were told that it had gone to the relevant department for consideration. A month of near-silence passed, followed by a month of absolute silence, followed—after one final query on our part, just this morning—by news that space could not be found.

Be that as it may, people are still being misled, so here’s our letter, as submitted on October 19, 2023. We realize that our circulation doesn’t quite equal that of the New York Review, but we do make every effort to keep the public record straight, and to find space for the truth.