THE INSTRUMENT

Throughout her career, Clarke played a Grancino that her father bought in Italy for £40, thinking it was an Amati. Hill & Sons, the preëminent London dealer, disagreed. Papa quibbled, but Hill’s better judgment—and cooler heads—prevailed.

The instrument is relatively small, at 16¼ inches. Subsequent owners describe a “very chocolatey, very beautiful sound, and very even,” but without a great deal of edge—an assessment confirmed by Clarke’s few known recordings (see here, under “Clarke as Performer”). Unlike her frenemy Lionel Tertis, she was almost exclusively concerned with chamber music, both as a performer and as a composer, and she was rarely afflicted with today’s enormous rooms, so the Grancino was probably ideal for her purposes.

Click on any image for a captioned slideshow, then click the “ℹ︎” button.

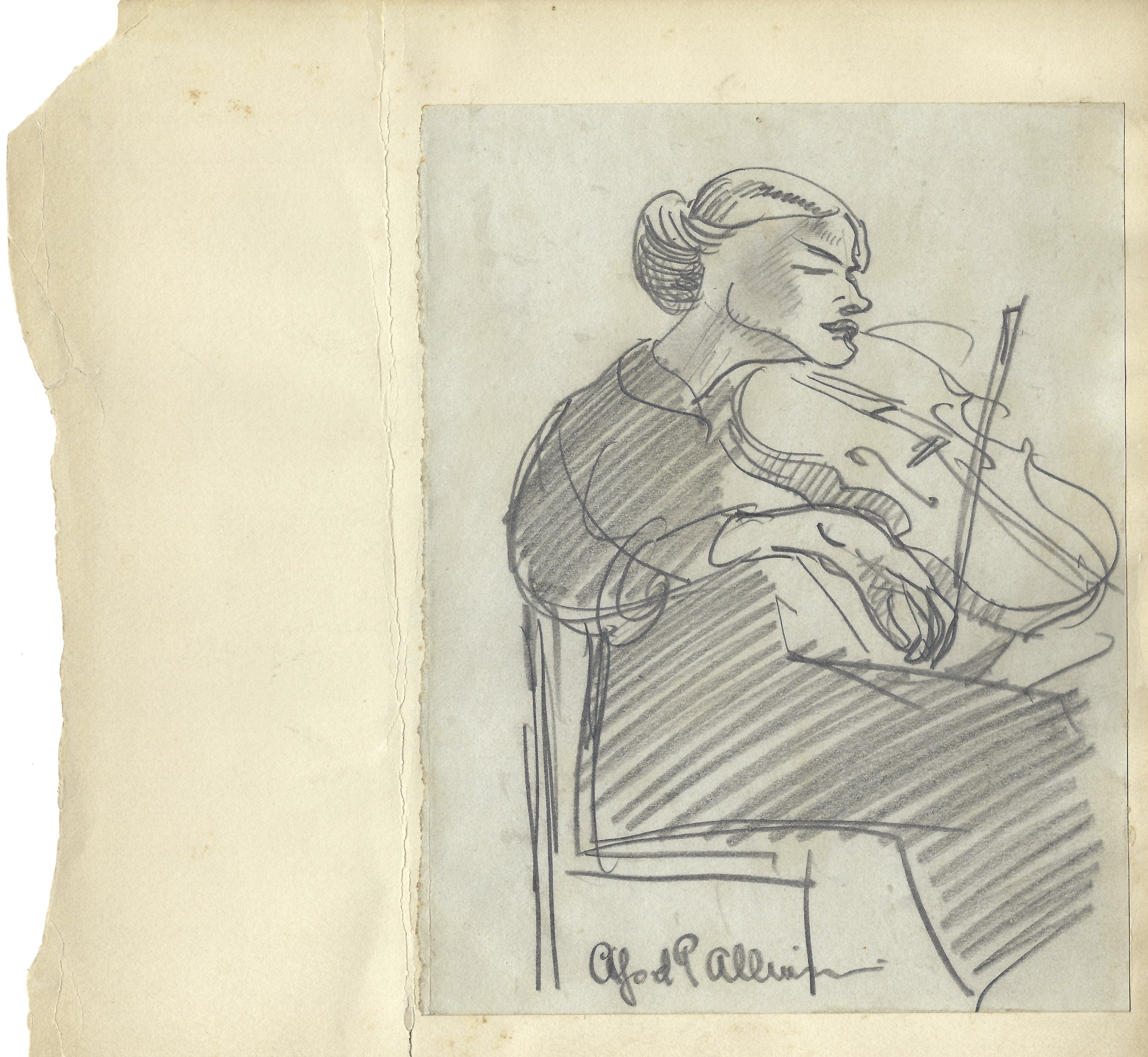

THE PLAYER

“The viola,” Clarke wrote, “is an exhausting instrument at the best of times.” Luckily, she stood nearly six feet tall and had extraordinarily long, graceful arms and fingers, so the instrument suited her physically, and looked good in her hands. The combination made a striking stage-picture—in recital, according to one awestruck witness, “she looked for all the world like the goddess Athene come down to mix with mortals. She had on a wonderful dress of the purest green, like the green of the rainbow [very likely the dress shown in the Hopkins Studio portraits shown below], and I can’t tell you how she looked in the face, so very very sweet.” Even as an orchestral player, she knew how to dress up her regulation “blacks” with a snazzy lace bertha—and for more on that, see Emily Brayshaw’s fascinating “Dressing for the Viola” (Journal of Dress History 7/3, Autumn 2023). At a more practical level, Clarke deliberately undermarked her publications, so as not to bind performers with different frames.

Click on any image for a captioned slideshow, then click the “ℹ︎” button.

THE METHODS

Little of Clarke’s playing was recorded, and none of that features her in a leading role, so we are left with second-hand accounts of her skills, methods, and tone, and—perhaps more instructive—with the markings in her performance-materials, upon which Caroline Castleton based her brilliant dissertation recital, entitled Rebecca Clarke, the Violist: A Pioneering Performance Career, at the University of Maryland, College Park, in 2023. Castleton’s program-note is enormously instructive, and her dissertation (follow the links here) is vital reading for anyone seriously interested in Clarke, from any perspective, but it’s the music that really begins to tell us who Clarke was as a viola-player.

THE SOUND, AS DESCRIBED BY CONTEMPORARIES

“Miss Clarke masters the deep ‘cello tones, as well as the song-like upper register of her instrument, and with more flexibility of bow phrasing will become an executant of real authority.”—New York Tribune, February 14, 1918

“Miss Clarke, who is an artist of high attainments, possesses a tone of great purity, impeccable intonation and pronounced interpretative ability.”—Musical Courier, February 21, 1918

“Her beautiful viola gives tones of haunting sweetness—at times it is a miniature ‘cello and again a master violin.”—Berkshire Evening Eagle, quoted in The Musical Leader, August 22, 1918

“With a wonderful instrument, a fit exemplar of that sister of the violin which unites sonority with sweetness and tonal dignity with fire and verve, she deserved the hearty applause which greeted both numbers (Wolstenholme’s ‘Romanza’ and Hayd[n]’s ‘Capriccio’) and after the latter the audience clamored for more.”—Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 21, 1919

“In the Romanza Miss Clarke drew out a peculiarly lovely and appealing tone of velvety smoothness and golden richness. The Capriccio was dainty and beautifully rendered.”—Pacific Commercial Advertiser, November 2, 1918

“There is no space here to . . . do more than record the names of a few who did not suffer from that disability [of faulty intonation]. . . . Among string players . . . Miss Rebecca Clarke . . . [playing her] sparkling viola sonata.”—Times (London), June 4, 1920